Mike Allison of Jelen Deer Services looks at our historical fasciniation with antlers, and looks in depth at their biological cycle

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Deer antler has featured in the lives of humans for thousands of years, evidenced from the cave paintings by ancient man. From heraldry and the many coats of arms in existence through to the modern-day hunter’s trophy room wall, the fascination with deer and their antlers is clear to see.

Deer antlers have played a large part in our development as a species, as part of our culture through the ages and ultimately – but sometimes contentiously – as an object of our desire.

Once used as essential farming tools and weapons, antlers were chosen for their almost perfect form for handling while undertaking tasks such as cultivation or digging, and not least for their strength as weapons through the Middle Ages.

Few people appreciate just how robust deer antler is compared to human bone, or indeed other bones in the deer’s body, being able to withstand the sometimes incredible impact typical when two stags clash head-on.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Antler composition

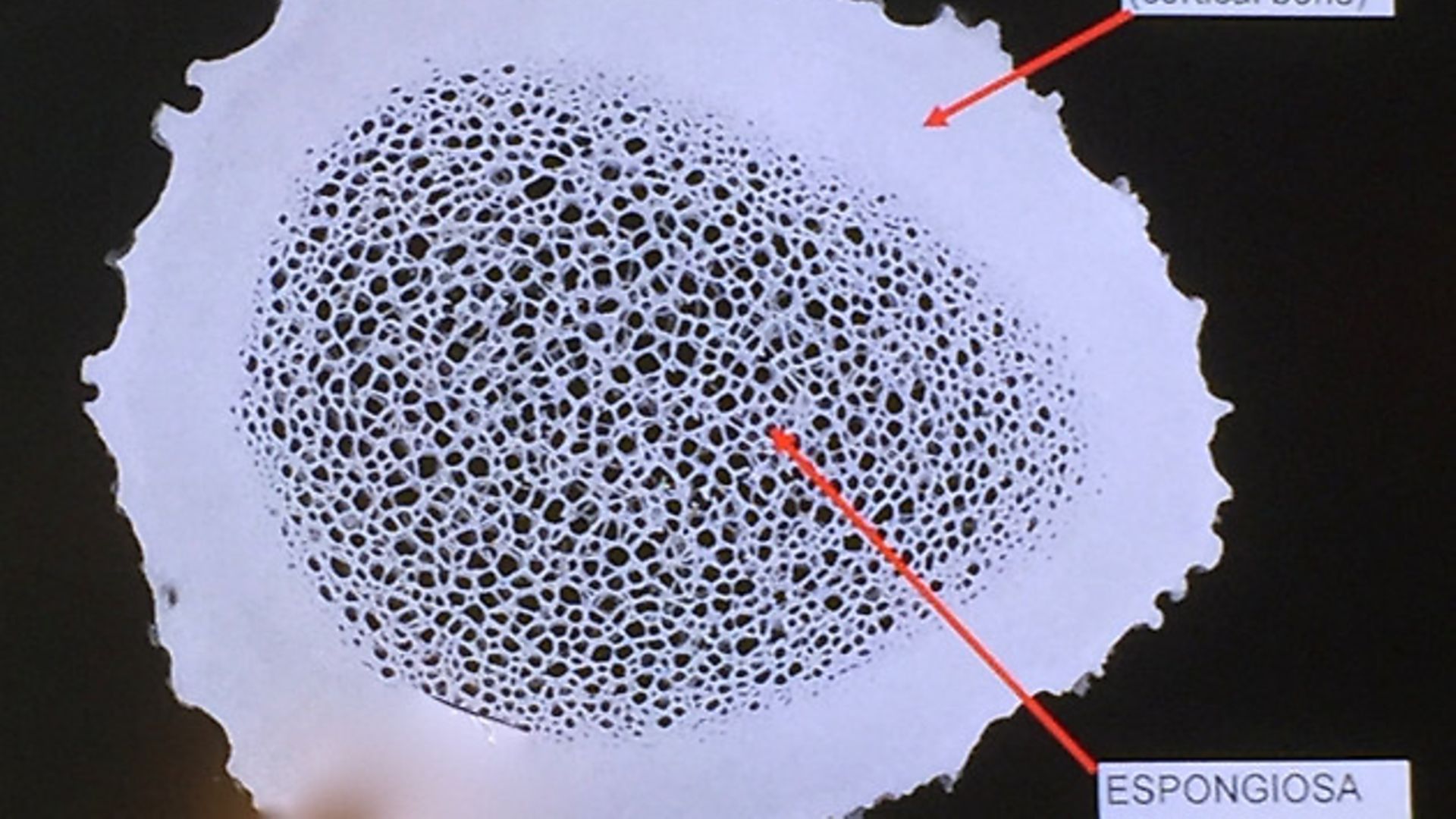

Antler consists of two distinct types of bone: compact or cortical bone (the outer wall), and trabecular, or spongy bone (the inner core). In species such as Pere David’s deer, the antler can be incredibly heavy and dense. It’s all down to the thickness of the cortical wall and the level of porosity in both the cortical and trabecular bone.

From the extensive research carried out in recent years, it is clear that the porosity of antler has a correlation with mechanical strength, and explains why highly porous antler is weak and lacking in weight, compared to antler of low porosity.

While there are prominent genetic influences involved with the style and size of antler growth, in most cases the porosity, weight and therefore strength of antler is almost always related to feed availability, quality, and nutritional value. Naturally, mineral content is a crucial influence – although the relationship between the various minerals and trace elements is extremely complex.

In this article we look at how antler grows and what you as a deer manager can do to improve antler growth and trophy weight.

To understand how to promote and improve antler growth, it is important to understand the growth pattern of antler immediately after casting. But to fully visualise the growth process, it is probably easier to understand if we discuss the antler casting first.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Antler casting

Antlers are normally cast annually, although in some species, such as Pere David’s deer, they have been observed to grow and cast three sets in two years.

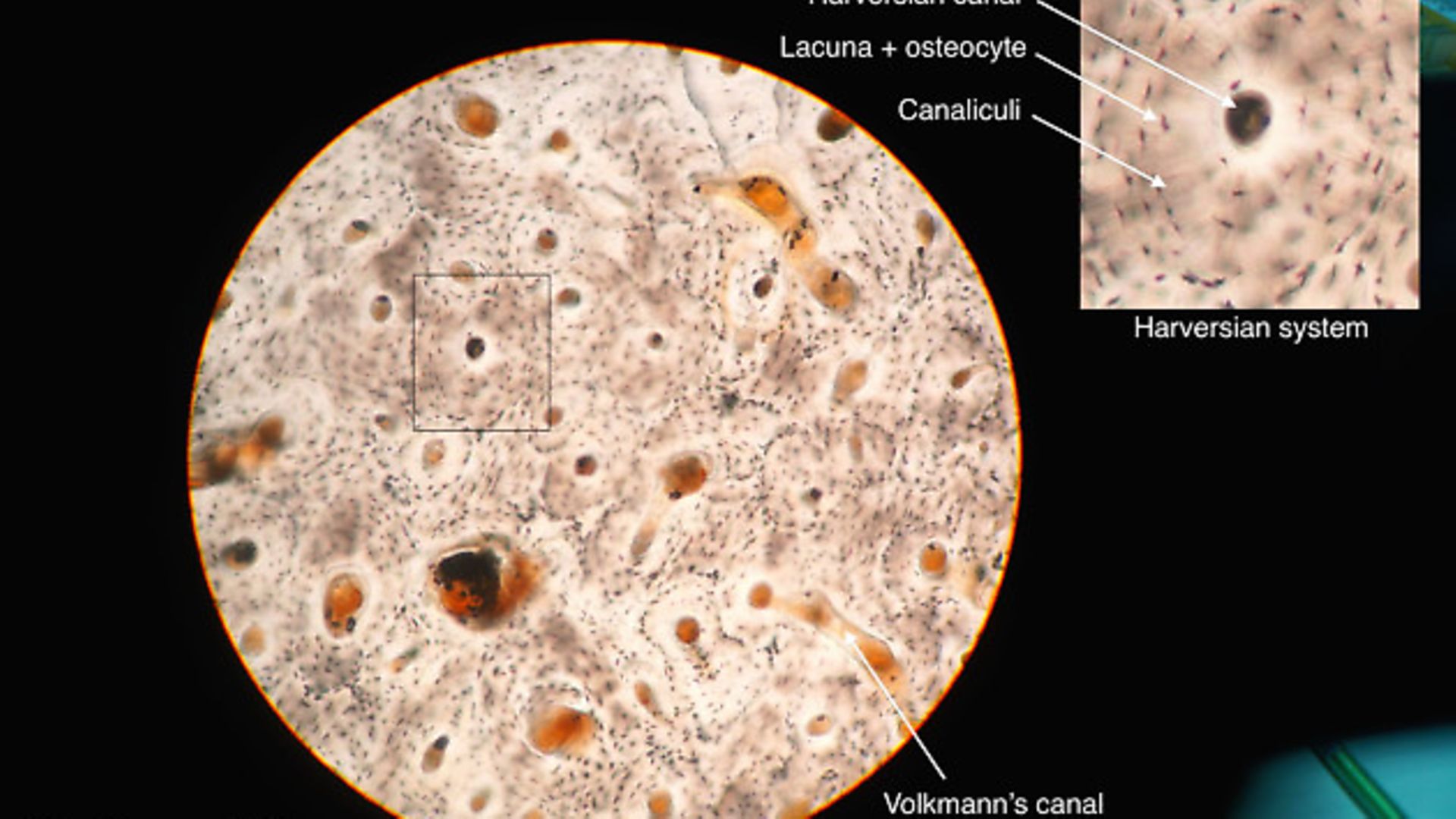

The process of casting is characterised by immature woven bone and primary osteons being destroyed by large ‘bone-eating’ cells called osteoclasts. These hollow out channels through bone, travelling mainly through existing blood vessels called Haversian canals.

As the layer of bone beneath the coronet of the antler is degraded by the osteoclasts, this substantially weakens the bone structure and the weight of the antler assists final breakage.

It is not unusual to find cast antlers near fences where stags/bucks have jumped the fence and the sudden jolt at landing has been enough to break the fragile junction between pedicle and coronet. Each year the pedicle can become shorter where a thin layer of the pedicle bone is destroyed, and this explains why older deer generally have shorter pedicles.

Once the antler has cast, then the osteoclasts are followed almost immediately by bone-forming cells called osteoblasts. These begin to lay down new bone along the sides of the hollow channels – and the new growth begins.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Antler growth

The whole cycle – from velvet, to shedding, to antler casting – is largely governed by the levels of testosterone in the body. However, the way in which the antler grows and its eventual form is without doubt influenced by genetics and management – i.e. its genotypic form plus what goes in through the mouth.

From the moment of casting, the growing cycle begins almost immediately, and within only a few days velvet will start to appear. Velvet grows distally to begin with, and at its full growing capacity the antlers of well-fed red deer can be growing at the rate of around one centimetre per day.It is important for the serious deer manager and trophy producer to understand the factors that affect antler growth and bone calcification processes. There is a strong economic case for maximising antler development and structure, as trophy value alone can represent a major income stream for many estates, often realising incomes ranging from £1,000 to well over £3,000, depending on the species.

To illustrate the difference in income that can occur, a good example would be to consider the trophy value of a roe buck on poorer nutrition compared to one on a high nutritional plane. For example, if we consider a 500g trophy head with only 5% porosity, then that would equate to a value to the landowner of £1,000 plus; however, where the antler is 60% porosity, the relative value for what is essentially the same physical size of head is around 50% less than its potential value. This net loss to landowners is avoidable.

The additional cost of feed and minerals is alleviated when related to the potential increase in trophy value. That is a simplistic view of how antler porosity can be inversely related to income potential, although we do need to consider how to get the necessary minerals and nutrition into the animal in the first place. Understanding of deer feed requirements and feeding behaviour will help deer managers to make the best use of supplementary feed.

Achieving these incomes from deer trophies is dependent on an accurate assessment and measurement of the head. This is usually in the form of a combined measurement of beam length, width, number of points, aesthetic quality and, not least, the antler weight. The weight of antler is directly related to the thickness of the cortical bone wall and its relative porosity.

In most cases, the thickness of the cortical wall reduces progressively up the antler beam and can range from five-and-a-half millimetres thick at the base to only three millimetres at the tops.

All antler tissue is porous to an extent and porosity is an enemy of the trophy producer, significantly reducing trophy quality and scoring. There are significant variations in the porosity of antler, dependent on nutrition management. In well-fed, farmed deer the porosity of cortical bone can vary between one and two per cent at the burr to around six per cent below the crown. In contrast, the antlers of deer subject to poor nutrition and/or mineral deficiency can be as much as 20%, and can result in underdeveloped tine ends, breakages, and in the summer the antler can be more susceptible to damage by fly strike. The normal range for cortical bone is five to 10% porosity, while trabecular bone can range from 50% to 90%. In summary, the weight of hard antler is dependent on good genetics, diet and management.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Mineralisation and calcification process – The antler growth stages

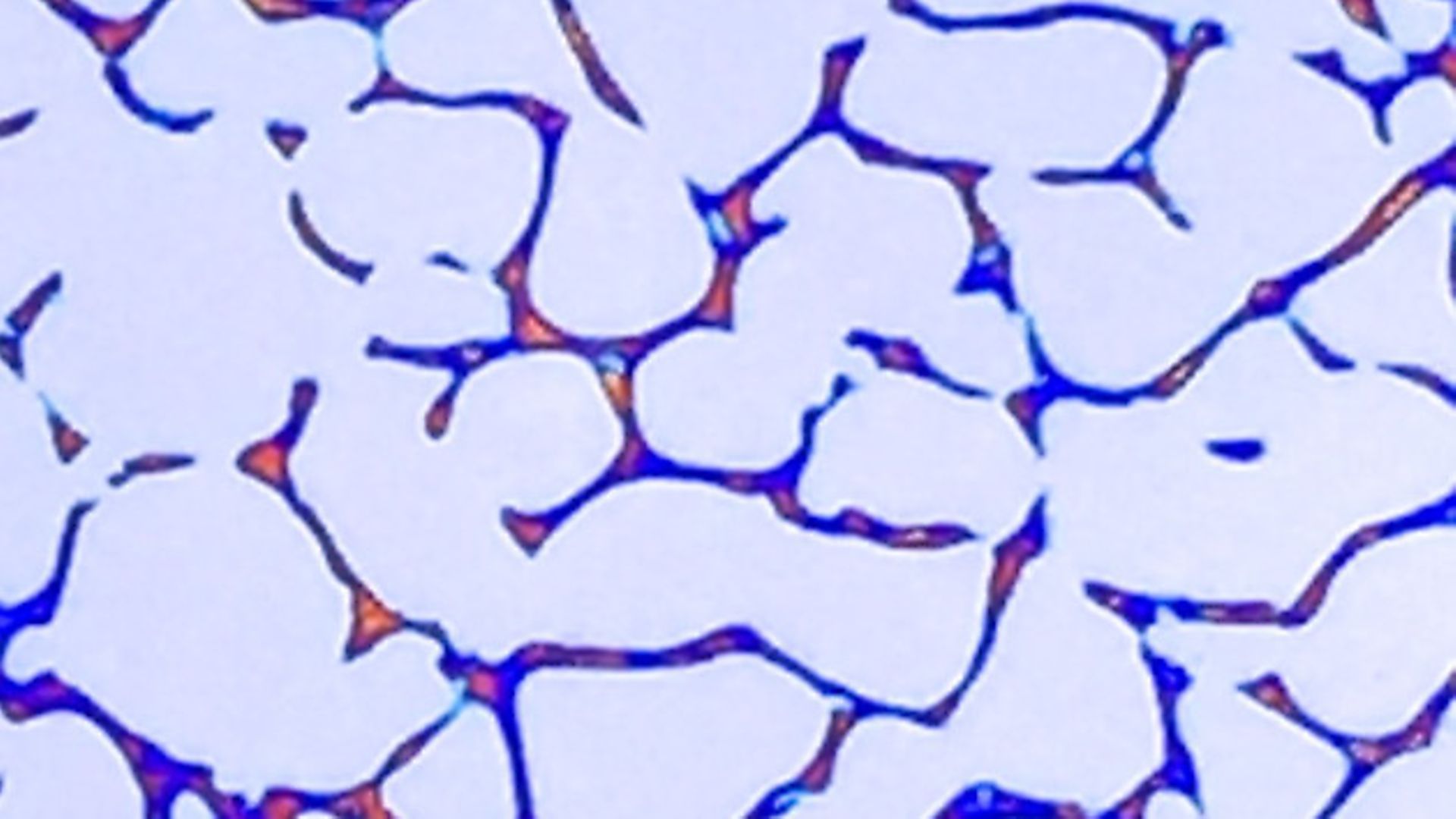

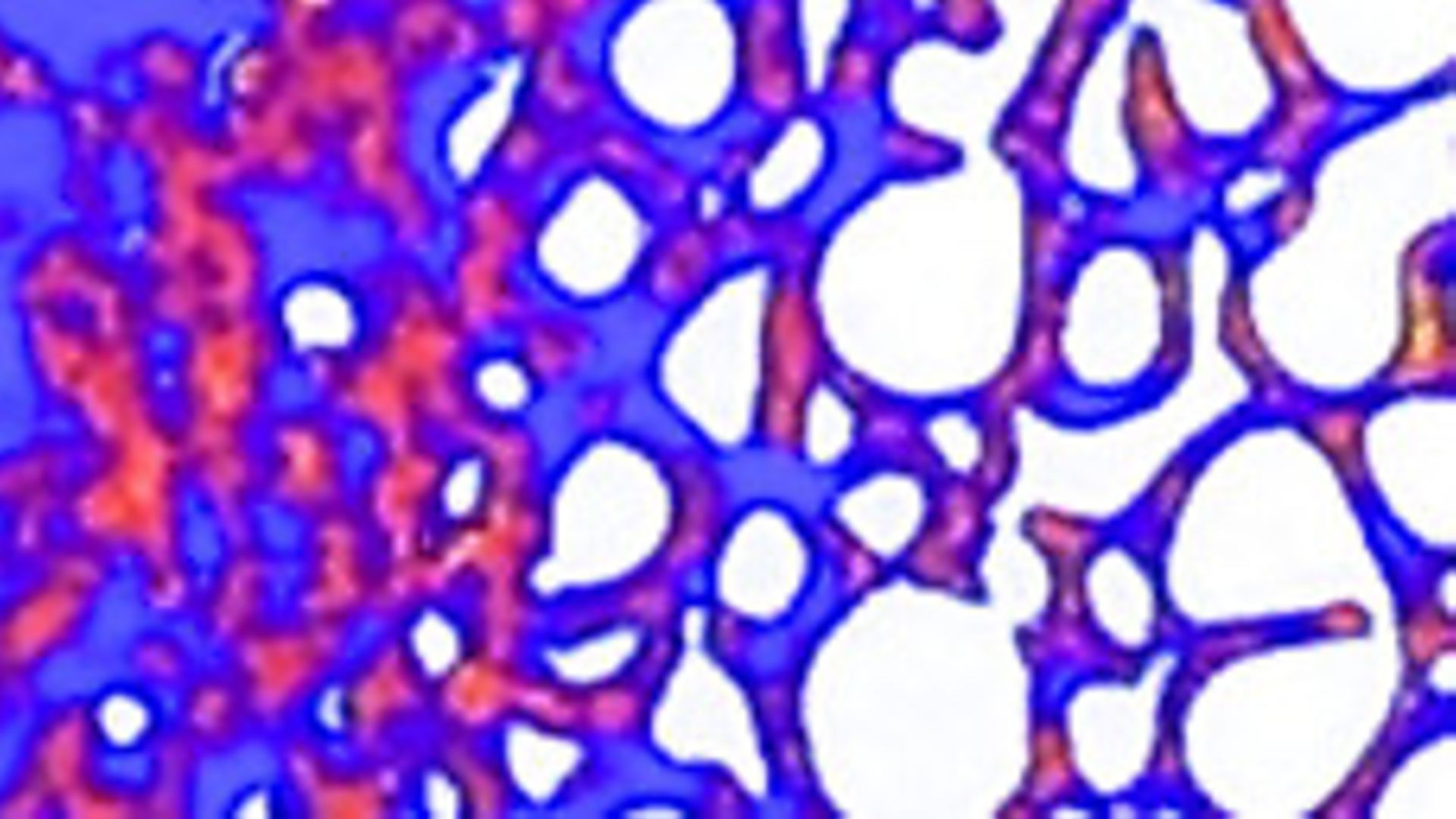

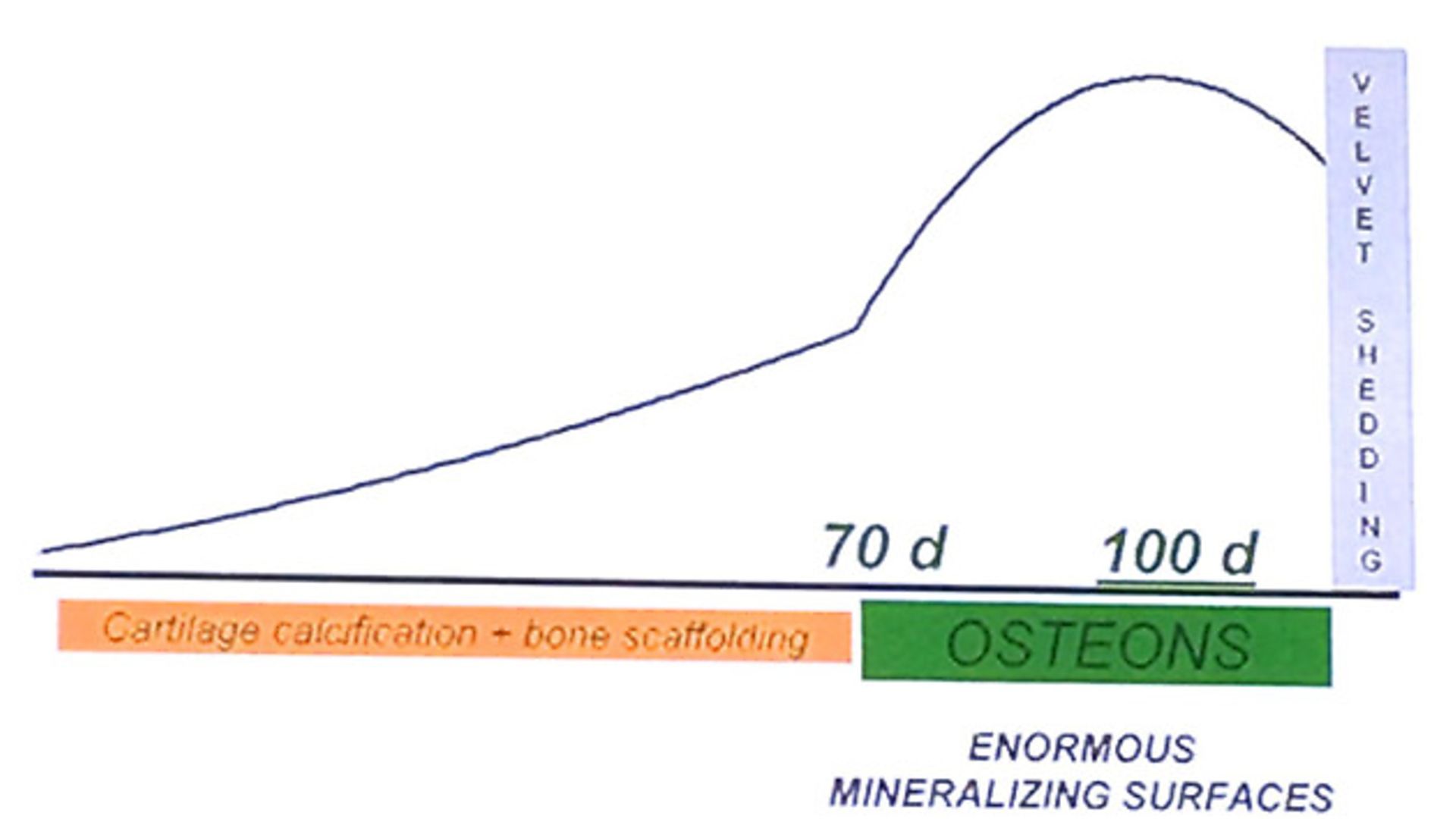

There are two distinct growth stages of antler between the beginning of new growth and velvet shedding.

? Development of bone scaffolding and calcification (zero to 70 days) – This stage is the most crucial period when the foundation for the antler is formed. It is during this period when there is the greatest demand for minerals from the deer’s body. One of the functions of the skeletal bones is the storage of minerals, and it is important that a residual store of minerals is available before antler growth is initiated.

? Surface mineralisation (70 to 100 days) – Rapid mineralisation takes place, resulting in structural changes as the antlers harden.

Where there is a shortfall in feed quality and the consequent nutritional benefit, then the growth stages will be inhibited, leading to underdeveloped trophies. This effect can happen during hard winters followed by a cold spring, or where animals go into the winter in substandard condition. They are unable to regain condition and achieve adequate mineral storage before the weather deteriorates and food availability decreases.

In such cases, the animal will devote much of its nutritional intake into producing energy to keep warm, rather than skeletal development – which includes antlers.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Velvet and velvet shedding

The growing antler is full of blood vessels and nerves. It is covered with a soft, hairy skin called ‘velvet’, which is warm to the touch and relatively fragile. All male antlered deer are careful not to damage their growing antlers and so they generally prefer areas where they are least likely to be disturbed.

During the Prime Development Period (PDP) (zero to 70 days) the growth process is akin to building a concrete structure, whereby the scaffolding, shuttering, reinforcements and framework are developed first. During the Secondary Development Period (70 to 100 days) is when the framework is effectively ‘filled’, and the true bone is made.

The antler hardening process is influenced by decreasing daylight hours, detected by the pituitary gland in the brain. This stimulates the consequent increase in testosterone levels in the body. In the latter stages of growth, the blood vessels calcify from the ends of the tines progressively down to the antler base.

This restricts the flow of blood and nutrients that the velvet needs in order to live. As a result, the velvet dies off, loosens and is easily rubbed off on vegetation, shrubs and trees. It is often eaten by the deer and other animals as it is highly nutritious.

The larger deer species (red, fallow and sika) are generally in hard antler by the end of August, with the older animals shedding velvet first. It is at this stage that an increase in fraying damage to trees occurs. While it is reasonable to assume that deer fray and rub trees simply to remove velvet, the fact is that over 90% of rubbing occurs after the velvet has been shed.

The increasing daylight hours coupled with a fall in testosterone levels are what stimulates the osteoclasts to the seam between the living tissue (pedicle) and the dead bone (antler). The antler eventually falls off and the antler cycle begins once more.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Mechanical strength of antler

While it would be perfectly logical to assume that the porosity of cortical bone would be a major influence in antler strength, it is not the only factor involved.

Mineral composition, especially zinc (Zn) and potassium (K), along with other minerals, almost certainly affect mechanical strength.

Therefore, it goes without saying that the animal’s intake of both nutritional feed and minerals are equally likely to affect the physical strength of the antler. Incidences of antler breakage are inversely related to trophy value.

From an economic standpoint, it makes perfect sense to ensure that animals are provided with a level of nutrition and minerals to encourage antler growth and quality through the unsuppressed development of primary osteons – the basic building blocks of cortical bone.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Influences on antler size

There are three fundamental factors that influence antler size: time, genetics and nutrition. In simple terms, the older a stag/buck gets, the larger the antlers grow until it reaches about four and a half years old.

A male roe deer, for example, will have grown his first set of antlers at the age of 18 months (one-and-a-half years), and normally he will have grown four points – occasionally six points – and the antler beam diameter will be in the region of 10mm.

By the time he reaches 30 months (two-and-a-half years), the antlers would have increased to six points and the beam diameter to 20mm.

The antler size and number of points will increase progressively until the animal reaches 42 months (three-and-a-half years). From then on the growth progression levels out and there is little increase in the number of points, or changes to antler characteristics.

Although subsequent antler weight increases year on year, the proportion of the increase is relatively small in comparison to the PDP between one-and-a-half and three-and-a-half years of age.

Most deer reach their peak of antler development at around five-and-a-half and seven-and-a-half years of age. From then on there is a gradual decline in antler quality year on year as the animal ages.

With this in mind, the PDP is the only chance that the deer manager will have to truly influence antler development, and therefore trophy quality, as it is the period when the framework is built.

Summary

To grow top-quality antlers, the serious deer manager can provide everything the animal needs in order to maximise antler growth, but there is no substitute for time!

There are no top trophy deer under three-and-a-half years old, and there will be no top trophy deer over four-and-a-half years of age unless antler growth is managed carefully during the PDP. Good feeding is the key.